Today, Brain Pickings reminded me it was the death-a-versary of one of my favourite writers. I’ve been thinking about Sylvia Plath a lot. In a workshop last week, I played a recording of her reading “Daddy”. It landed in the room like something foul, something rotten. Faces were made, awkward shiftings in fold-down chairs in the lecture hall. Not a one of the students liked it and I wondered why. Perhaps there is something about her voice, arch and brittle, distinctly New England, that put them off? Maybe they’d already had too much of her at A-level or maybe, I thought with horror, they couldn’t relate her anymore, that time had eroded her power or interest, that she was dated, passe’, irrelevant. Could it be so – for them?

Sylvia Plath died before I was born and I cannot get enough of her. We all have triggers, things that will make us pick up a book faster than seems humanly possible. I tell myself I know everything there is to know about Sylvia Plath – poetess and cuckold, doomed wife and mother, misunderstood teen-woman with her oven and her milk and cookies and her tragic rolls of tape – but she is my trigger. Any reference to her on a jacket, in a blurb, and the book is at the till with my debit card out faster than you can say Lady Lazarus – but why? Why does she have such a hold on me, still?

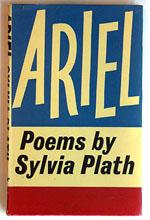

Ariel set me on the road to feminism. A budding playwright, I was a Ted-hater way back, in emotional solidarity with those who repeatedly scratched the Hughes from her tombstone. I have long since repented of this vandalism; I do adore Ted Hughes, though not nearly with the passion I reserve for Sylvia. On a recent residency at Yaddo, whose bedroom did I need to see first? Whose books did I search for at the library? Reader, it was I. At Yaddo, Plath wrote poems for The Colossos, for Ariel was still many dark winters ahead of her, and spent eleven weeks working alongside Hughes in what seems to be a happy time for both of them; she writes often of their stay in Letters Home, the collection of her correspondence from 1950 – 1963. The knowledge that she had stood in the library, running her fingers along the spines, was thrilling. Reading my work aloud in the room where I knew she had nearly undid me.

Ariel set me on the road to feminism. A budding playwright, I was a Ted-hater way back, in emotional solidarity with those who repeatedly scratched the Hughes from her tombstone. I have long since repented of this vandalism; I do adore Ted Hughes, though not nearly with the passion I reserve for Sylvia. On a recent residency at Yaddo, whose bedroom did I need to see first? Whose books did I search for at the library? Reader, it was I. At Yaddo, Plath wrote poems for The Colossos, for Ariel was still many dark winters ahead of her, and spent eleven weeks working alongside Hughes in what seems to be a happy time for both of them; she writes often of their stay in Letters Home, the collection of her correspondence from 1950 – 1963. The knowledge that she had stood in the library, running her fingers along the spines, was thrilling. Reading my work aloud in the room where I knew she had nearly undid me.

Many come to Sylvia through The Bell Jar, which seems to have become a YA book since I was a young adult. Were I one now, I might have found my way to Plath through Meg Wolitzer’s Belzhar, where traumatised teens in a New England boarding school find peace and connection though Special Topics in English and a journal they must fill. Of course, the journal affords them magical adventures of memory, time travel, and redemption, and I loved it. There isn’t a huge amount of Plath in this Belzhar, but I think she’s there in that teenage passion, the wounds that cut and refuse to heal, memories that feel as if the world has ended, before we outgrow such wonderfully painful things.

Many come to Sylvia through The Bell Jar, which seems to have become a YA book since I was a young adult. Were I one now, I might have found my way to Plath through Meg Wolitzer’s Belzhar, where traumatised teens in a New England boarding school find peace and connection though Special Topics in English and a journal they must fill. Of course, the journal affords them magical adventures of memory, time travel, and redemption, and I loved it. There isn’t a huge amount of Plath in this Belzhar, but I think she’s there in that teenage passion, the wounds that cut and refuse to heal, memories that feel as if the world has ended, before we outgrow such wonderfully painful things.

Recently, I found a young Sylvia in Pain, Parties, Work: Sylvia Plath in New York, Summer 1953. Elizabeth Winder painstakingly reconstructs four weeks in Plath’s life as a guest editor for the Mademoiselle magazine’s annual college issue, inspecting and illuminating events from her point of view, through her journals and letters, as well as interviewing fellow guest editors, some of whom would end up, often only slightly rewritten, in The Bell Jar. There are wonderful photographs, sidebars on period culture and fashion, and kernels of the work to come, as well as a thorough examination of what seems to have been expected of women at the time and how Plath was already balking.

Of course, there are a kabillion biographies of Sylvia Plath, and they’re all good, in their various ways, combing over the wealth of materials and journals and diaries that she produced. Leaving those to one side, I admire works that are inspired by her, that strive to feel like her. Kate Moses’ Wintering is a “novel of Sylvia Plath”, set during the last few months of her life. Chapters are arranged in the order of the Ariel poems as Plath intended, not in the order of the collection as Hughes saw fit to publish after her death. You probably do have to be a hardcore Plath-fan to love Wintering, but there is much to admire. It isn’t easy. The terrain and the language are rich, dense, and evocative. Here and there, Moses does slip under the poet’s skin, right where we want to be.

Of course, there are a kabillion biographies of Sylvia Plath, and they’re all good, in their various ways, combing over the wealth of materials and journals and diaries that she produced. Leaving those to one side, I admire works that are inspired by her, that strive to feel like her. Kate Moses’ Wintering is a “novel of Sylvia Plath”, set during the last few months of her life. Chapters are arranged in the order of the Ariel poems as Plath intended, not in the order of the collection as Hughes saw fit to publish after her death. You probably do have to be a hardcore Plath-fan to love Wintering, but there is much to admire. It isn’t easy. The terrain and the language are rich, dense, and evocative. Here and there, Moses does slip under the poet’s skin, right where we want to be.

Often, Sylvia is only a ghost and no more so than in Ted Hughes’ Birthday Letters, published just months prior to his death. A collection of poems that he seems to have written over his long life, they show how he was haunted by her actions and his own. They show him trying to pin her down, to understand what happened and how he was, and was not, responsible. They are love letters and question marks, elegies to who she was and who he was. In last week’s workshop, I also shared a few poem by Ted Hughes – Pike and The Thought Fox – and told them the story of their marriage and its demise, and I thought again, as the students finally sat up with interest, how dogged the two were, and always will be, by the drama of their lives.

A recent addition to the Hughes/Plath canon is the novella/essay/fable/miracle by editor and writer Max Porter, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, wherein a black crow comes to rescue a man unhinged by the death of his wife and his two motherless boys. Crow, Hughes’ talisman, is billed as “antagonist, trickster, healer, babysitter”. He arrives at the door like a dark-winged Mary Poppins and says he will stay until they don’t need him anymore. Throughout the book, Crow teases, soothes, and torments them, inserts himself into poetry and history, and helps them remember how it feels to live. Reading it, having recently lost my own mother, I sobbed like a kitten. I can hardly bear to open the book now, but it went straight onto the shelf of favourite books in the Blue House and sits there now beside Mary Oliver and Louise Erdrich and my battered copy of Ariel, all flanking a faded, curling picture of me as a child, head bent, examining my thumb with pain and wonder – a first splinter or graze, I think, the moment where I seem to understanding something about the world and deciding whether or not I will cry. There is something about pain and wonder in all of these books. Is it any wonder I keep going back to them, sharing them with students, and holding them so close?

A recent addition to the Hughes/Plath canon is the novella/essay/fable/miracle by editor and writer Max Porter, Grief Is the Thing with Feathers, wherein a black crow comes to rescue a man unhinged by the death of his wife and his two motherless boys. Crow, Hughes’ talisman, is billed as “antagonist, trickster, healer, babysitter”. He arrives at the door like a dark-winged Mary Poppins and says he will stay until they don’t need him anymore. Throughout the book, Crow teases, soothes, and torments them, inserts himself into poetry and history, and helps them remember how it feels to live. Reading it, having recently lost my own mother, I sobbed like a kitten. I can hardly bear to open the book now, but it went straight onto the shelf of favourite books in the Blue House and sits there now beside Mary Oliver and Louise Erdrich and my battered copy of Ariel, all flanking a faded, curling picture of me as a child, head bent, examining my thumb with pain and wonder – a first splinter or graze, I think, the moment where I seem to understanding something about the world and deciding whether or not I will cry. There is something about pain and wonder in all of these books. Is it any wonder I keep going back to them, sharing them with students, and holding them so close?

My old ways weren’t working. There was no comfort to be found in writing – or reading. I didn’t know how to find the resilence to begin again – again – nor any idea of how to quit. Salvation came in an email from

My old ways weren’t working. There was no comfort to be found in writing – or reading. I didn’t know how to find the resilence to begin again – again – nor any idea of how to quit. Salvation came in an email from  It didn’t, of course. It ended last night in its own watery grave, as did the month of January, a horrible month for so much of the world. One twelfth of a new year, done and drowned. But somehow, in the last week of January, I found myself able to return to a project that broke my heart. I know it will continue to break my heart a few more times before it’s done with me, but somehow, with the passing of time and the lifeblood of a leviathan, I feel able to get back on my boat, board my craft and try to sail it. (Too many metaphors? Too many parentheses? Blame Melville. And I wouldn’t be surprised if he pops up again for me, down the road, in another project that lies ahead, if I can get on the other side of the books I must write first. There is a quite a queue building.) “For the third time my soul’s ship starts upon this voyage, Starbuck.” If Captain Ahab can give his whale three chases, I reckon I have another draft in me.

It didn’t, of course. It ended last night in its own watery grave, as did the month of January, a horrible month for so much of the world. One twelfth of a new year, done and drowned. But somehow, in the last week of January, I found myself able to return to a project that broke my heart. I know it will continue to break my heart a few more times before it’s done with me, but somehow, with the passing of time and the lifeblood of a leviathan, I feel able to get back on my boat, board my craft and try to sail it. (Too many metaphors? Too many parentheses? Blame Melville. And I wouldn’t be surprised if he pops up again for me, down the road, in another project that lies ahead, if I can get on the other side of the books I must write first. There is a quite a queue building.) “For the third time my soul’s ship starts upon this voyage, Starbuck.” If Captain Ahab can give his whale three chases, I reckon I have another draft in me. After all, this isn’t a battle of life and death. I have no boatload of whalers to defend. I have only this great white whale of a story, trying to run away from me, and the harpoon of my desire to catch it. If it doesn’t end well for Ahab – or the whale – I won’t dwell on that. In my mind, there is another life for the crew of the Pequod, Melville’s unwritten sequel. Of course, they escape defeat. Of course, they surface, once Ishmael has sailed away in his loneliness. Of course, Queequeg swims to a new island, bearing Stubb upon his back. Of course, Daggoo and Tashtego build the dug-out canoe that will take them all back to New England, where Ishmael awaits with a bowl of chowder. And Ahab? Of course, he will spend eternity circling his prize, which is as it should be, after all.

After all, this isn’t a battle of life and death. I have no boatload of whalers to defend. I have only this great white whale of a story, trying to run away from me, and the harpoon of my desire to catch it. If it doesn’t end well for Ahab – or the whale – I won’t dwell on that. In my mind, there is another life for the crew of the Pequod, Melville’s unwritten sequel. Of course, they escape defeat. Of course, they surface, once Ishmael has sailed away in his loneliness. Of course, Queequeg swims to a new island, bearing Stubb upon his back. Of course, Daggoo and Tashtego build the dug-out canoe that will take them all back to New England, where Ishmael awaits with a bowl of chowder. And Ahab? Of course, he will spend eternity circling his prize, which is as it should be, after all. I don’t often do author interviews on my blog, but here is a wonderful exception! One of the best parts of being a writer is the opportunity to make friends with other writers whose work you love. In honour of her upcoming appearance at Canterbury Christ Church, as part of the

I don’t often do author interviews on my blog, but here is a wonderful exception! One of the best parts of being a writer is the opportunity to make friends with other writers whose work you love. In honour of her upcoming appearance at Canterbury Christ Church, as part of the  The second spark, really more of a jolt of electricity, was a poster I saw in a window front in a junk shop in the Brighton Lanes. This image of Theda Bara – a goddess and vamp of the silent screen – went on to inspire the seductive dark looks of my novel’s main character, Leda Grey: a young girl who grows up while dreaming of becoming a star of the silent screen.

The second spark, really more of a jolt of electricity, was a poster I saw in a window front in a junk shop in the Brighton Lanes. This image of Theda Bara – a goddess and vamp of the silent screen – went on to inspire the seductive dark looks of my novel’s main character, Leda Grey: a young girl who grows up while dreaming of becoming a star of the silent screen. But, when writing my Victorian novels I also became very interested in the development of photography, and how that then led to moving film – the medium which has since gone on to have an enormous influence on so many aspects of our modern world. And yet, we know so little about the pioneers of early British film – and as Ed, who is a journalist who becomes obsessed with Leda Grey, says when he first hears of them: ‘Why don’t we know of this … I’d always assumed the silent films first started in America.’ Of course, Ed is speaking for me here. I’d imagined the Hollywood silents were all made in the 1920s, whereas the earliest moving films were Victorian and Edwardian – and they were made in England, in Europe, and other countries too – as well as in America.

But, when writing my Victorian novels I also became very interested in the development of photography, and how that then led to moving film – the medium which has since gone on to have an enormous influence on so many aspects of our modern world. And yet, we know so little about the pioneers of early British film – and as Ed, who is a journalist who becomes obsessed with Leda Grey, says when he first hears of them: ‘Why don’t we know of this … I’d always assumed the silent films first started in America.’ Of course, Ed is speaking for me here. I’d imagined the Hollywood silents were all made in the 1920s, whereas the earliest moving films were Victorian and Edwardian – and they were made in England, in Europe, and other countries too – as well as in America. A great many early film makers were involved in the photographic trade, or had had theatrical careers. Magicians like George Melies grasped this exciting new medium to expand the tricks performed on stage. And what wonders were achieved on film – with double exposures or split screens allowing the most surprising effects. I found it quite fascinating myself, to exploit so many of these themes when imagining all the old noir ‘films’ that I write about in Leda Grey – films with which have the illusions of ghosts, or men who’ve had their heads chopped off which they then juggle round like balls. And, whether directors made comedies, or stories with eerier atmospheres, the early effects that they devised are often still employed in today. Cruder, yes. Of course they are. The technology has come so far. But, still, remarkable to see.

A great many early film makers were involved in the photographic trade, or had had theatrical careers. Magicians like George Melies grasped this exciting new medium to expand the tricks performed on stage. And what wonders were achieved on film – with double exposures or split screens allowing the most surprising effects. I found it quite fascinating myself, to exploit so many of these themes when imagining all the old noir ‘films’ that I write about in Leda Grey – films with which have the illusions of ghosts, or men who’ve had their heads chopped off which they then juggle round like balls. And, whether directors made comedies, or stories with eerier atmospheres, the early effects that they devised are often still employed in today. Cruder, yes. Of course they are. The technology has come so far. But, still, remarkable to see.

What’s next for Essie Fox? This is my fourth novel, with the first being published in 2011. To be honest, I think I need a break – a chance to get out in the world a bit more, to see the friends and family I’ve neglected over the past five years. My house also needs some attention if I want to stop it crumbling and ending up in the same state as White Cliff House in Leda Grey. But having said that I already have at least three new ideas in mind. The question is can I resist the siren songs that are calling me?

What’s next for Essie Fox? This is my fourth novel, with the first being published in 2011. To be honest, I think I need a break – a chance to get out in the world a bit more, to see the friends and family I’ve neglected over the past five years. My house also needs some attention if I want to stop it crumbling and ending up in the same state as White Cliff House in Leda Grey. But having said that I already have at least three new ideas in mind. The question is can I resist the siren songs that are calling me? Yesterday, I was the special guest of

Yesterday, I was the special guest of  Isabel Costello is, of course, an author in her own right as well. Her debut, Paris Mon Amour, has received a clutch of fantastic reviews, such as this one from

Isabel Costello is, of course, an author in her own right as well. Her debut, Paris Mon Amour, has received a clutch of fantastic reviews, such as this one from  Here in London, my favourite library is a far cry from a dusty desert. Whenever I can, I trundle in to the wonderful

Here in London, my favourite library is a far cry from a dusty desert. Whenever I can, I trundle in to the wonderful